-40%

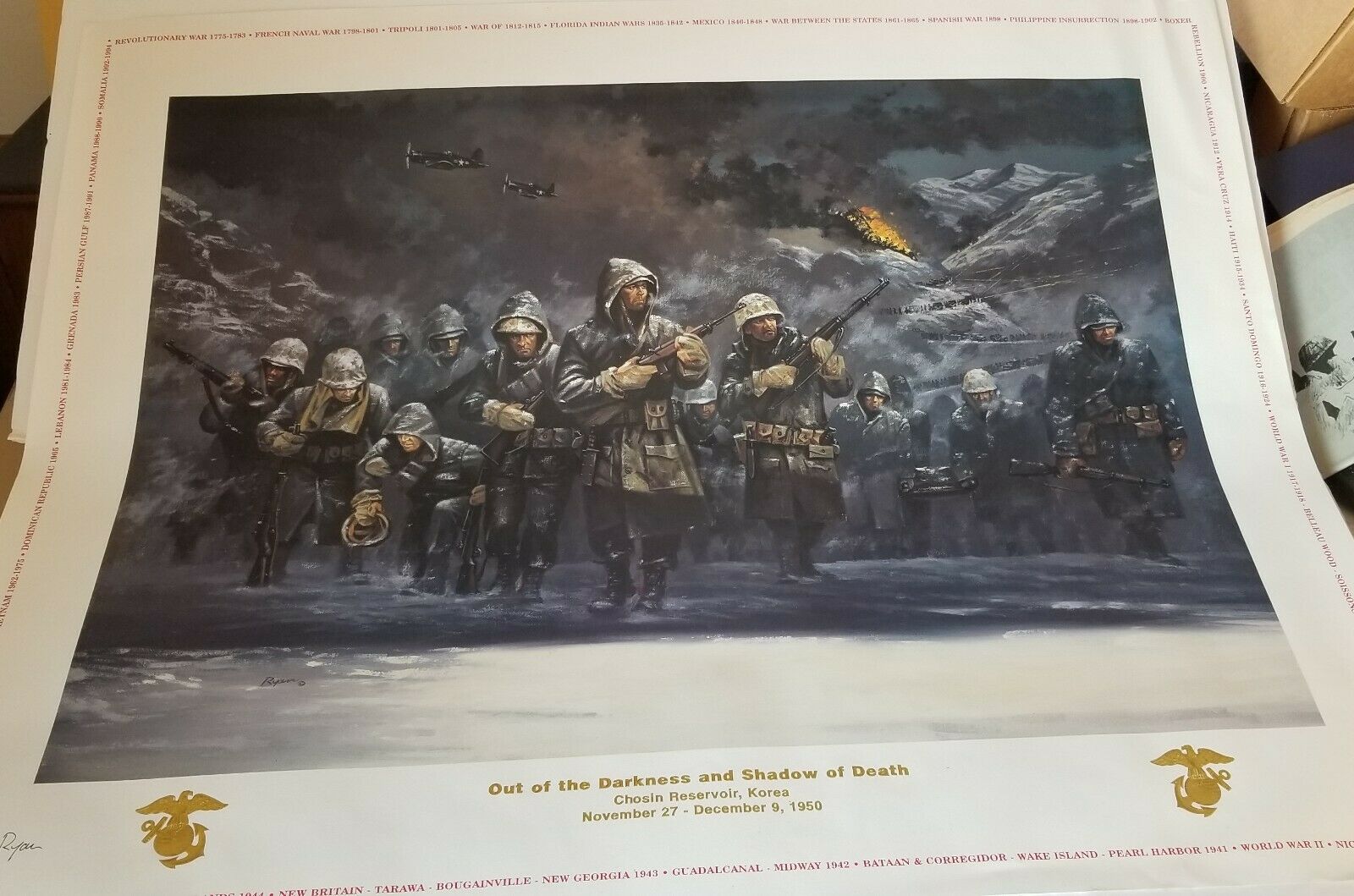

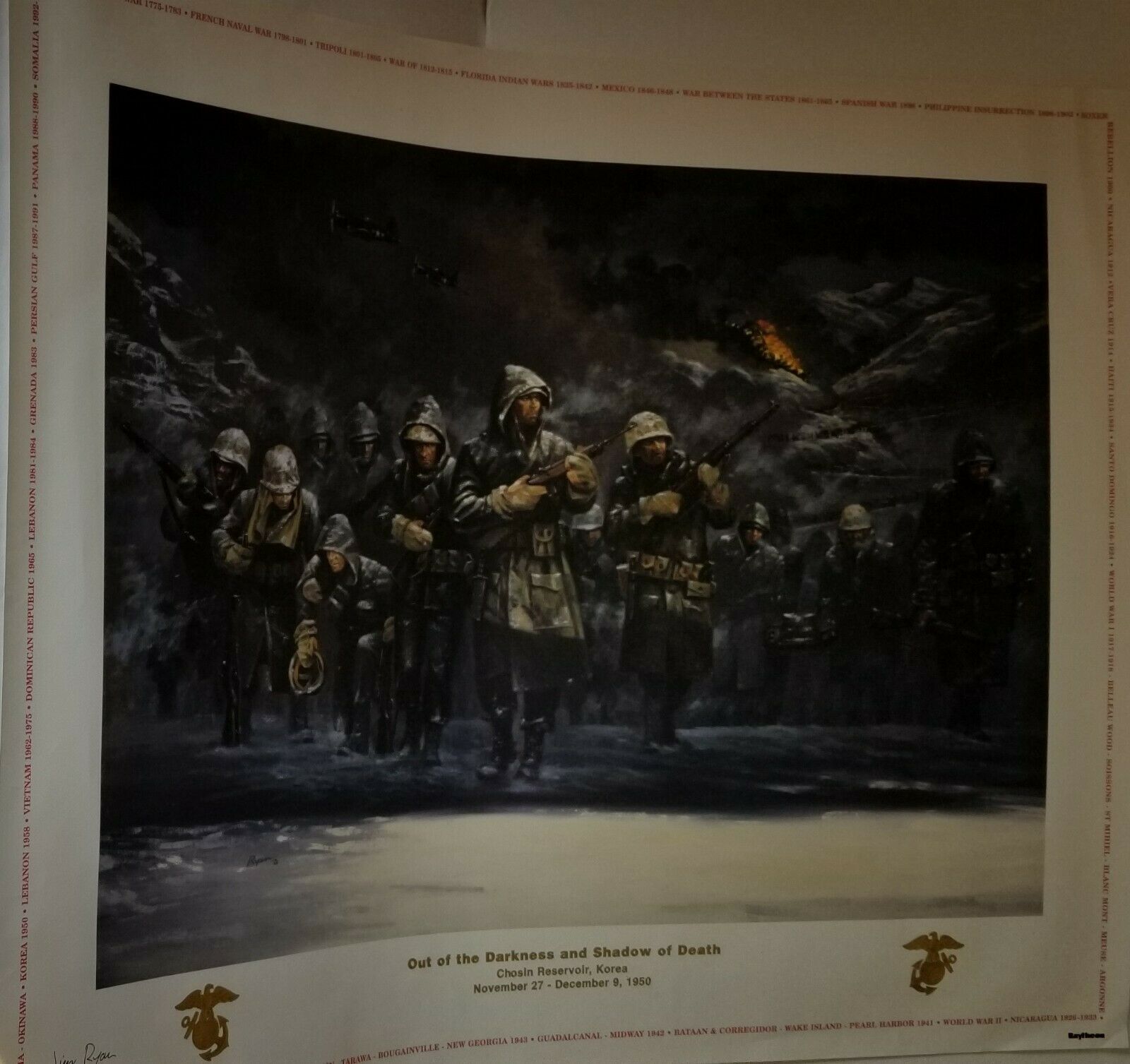

CHOSIN RESERVOIR - KOREA - 1950 - U.S. MARINE CORPS USMC RAYTHEON POSTER SIGNED

$ 31.67

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

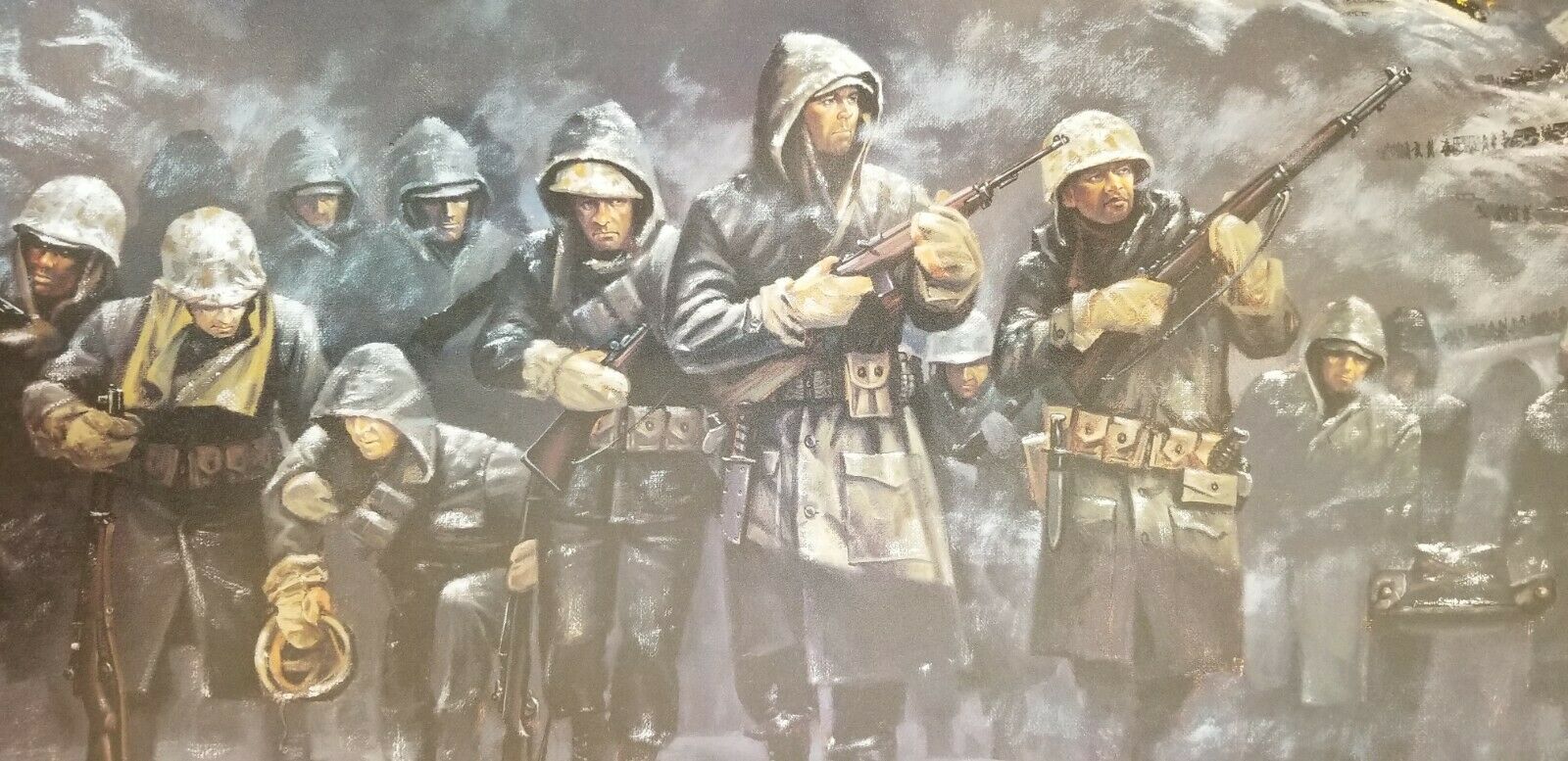

OUT OF THE DARKNESS AND SHADOW OF DEATH - CHOSIN RESERVOIR, KOREA. NOVEMBER 27 - DECEMBER 9, 1950. Signed art print. Signed by the artist Jim Ryan. This print was done by Ratheon in 2000. Measures 31" x 25". It has a light vertical crease in the top right corner and some edge imperfections - NONE of which affect the image. If you had it matted or framed you wouldn't be able to tell it was there.

Insured USPS Priority delivery in the continental US is $ 20.00.

Lore of the Corps

Starting in boot camp, all Marines study the actions of those who have served before them. The history of the Marine Corps is a rich tapestry weaving together the contributions of all Marines. Over the past two centuries, certain aspects of the Corps’ history have taken on an almost legendary status. Below are examples of some of the stories, terms, and traditions that have come to be known as the “Lore of the Corps.”

The Blood Stripe

Marine Corps tradition maintains that the red stripe worn on the trousers of officers and noncommissioned officers, and commonly known as the “blood stripe,” commemorates those Marines killed storming the castle of Chapultepec in 1847. Although this belief is firmly embedded in the traditions of the Corps, it has no basis in fact. The use of stripes clearly predates the Mexican War.

In 1834, uniform regulations were changed to comply with President Andrew Jackson’s wishes that Marine uniforms return to the green and white worn during the Revolutionary War. The wearing of stripes on the trousers began in 1837, following the Army practice of wearing stripes the same color as uniform jacket facings. Colonel Commandant Archibald Henderson ordered those stripes to be buff white. Two years later, when President Jackson left office, Colonel Henderson returned the uniform to dark blue coats faced red. In keeping with earlier regulations, stripes became dark blue edged in red. In 1849, the stripes were changed to a solid red. Ten years later uniform regulations prescribed a scarlet cord inserted into the outer seams for noncommissioned officers and musicians and a scarlet welt for officers. Finally, in 1904, the simple scarlet stripe seen today was adopted.

"Leatherneck"

In 1776, the Naval Committee of the Second Continental Congress prescribed new uniform regulations. Marine uniforms were to consist of green coats with buff white facings, buff breeches and black gaiters. Also mandated was a leather stock to be worn by officers and enlisted men alike. This leather collar served to protect the neck against cutlass slashes and to hold the head erect in proper military bearing. Sailors serving aboard ship with Marines came to call them “leathernecks.”

Use of the leather stock was retained until after the Civil War when it was replaced by a strip of black glazed leather attached to the inside front of the dress uniform collar. The last vestiges of the leather stock can be seen in today’s modern dress uniform, which features a stiff cloth tab behind the front of the collar.

The term “leatherneck” transcended the actual use of the leather stock and became a common nickname for United States Marines. Other nicknames include “soldiers of the sea,” “devil dogs,” and the slightly pejorative “gyrene,” (a term which was applied to the British Royal Marines in 1894 and to the U.S. Marines by 1911), and “jarhead.”

"Semper Fidelis"

The Marine Corps adopted the motto “Semper Fidelis” in 1883. Prior to that date three mottoes, all traditional rather than official, were used. The first of these, antedating the War of 1812, was “Fortitudine.” The Latin phrase for “with courage,” it was emblazoned on the brass shako plates worn by Marines during the Federal period. The second motto was “By Sea and by Land,” taken from the British Royal Marines “Per Mare, Per Terram.” Until 1848, the third motto was “To the shores of Tripoli.” Inscribed on the Marine Corps colors, this commemorated Presley O’Bannon’s capture of the city of Derna in 1805. In 1848, this was revised to “From the halls of the Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli.”

“Semper Fidelis” signifies the dedication that individual Marines have to “Corps and country,” and to their fellow Marines. It is a way of life. Said one former Marine, “It is not negotiable. It is not relative, but absolute…Marines pride themselves on their mission and steadfast dedication to accomplish it.”

"Devil Dogs"

According to Marine Corps tradition, German soldiers facing the Marines at Belleau Wood called them

teufelhunden

. These were the devil dogs of Bavarian folklore - vicious, ferocious, and tenacious. Shortly thereafter, a Marine recruiting poster depicted a dachshund, wearing an Iron Cross and a spiked helmet, fleeing an English bulldog wearing the eagle, globe and anchor.

A tradition was born. Although an “unofficial mascot,” the first bulldog to “serve” in the United States Marine Corps was King Bulwark. Renamed Jiggs, he was enlisted on 14 October 1922 for the “term of life.” Enlistment papers were signed by Brigadier General Smedley D. Butler. Although he began his career as a private,

Jiggs

was quickly promoted to the rank of sergeant major. His death at the age of four was mourned throughout the Corps. His body lay in a satin-lined casket in a hangar on Marine Corps Base Quantico until he was buried with military honors.

Other bulldogs followed in the tradition of

Jiggs

. From the 1930s through the early 1950s, the name of the bulldogs was changed to Smedley as a tribute to Major General Butler. In the late 1950s, the Marine Barracks in Washington became the new home for the Marine Corps’ bulldog. Chesty, named in honor of the legendary Lieutenant General Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, Jr, made his first public appearance on 5 July 1957.

Today the tradition continues. The bulldog, tough, muscular and fearless, has come to epitomize the fighting spirit of the United States Marine Corps.

8th and I

A notice posted in the Washington newspaper National Intelligence on 3 April 1801 offered “a premium of 100 dollars” for the “best plan of barracks for the Marines sufficient to hold 500 men, with their officers and a house for the Commandant.” The site for the barracks, near the Washington Navy Yard and within marching distance of the Capitol, was chosen by President Thomas Jefferson, who rode through Washington with Lieutenant Commandant William W. Burrows.

The competition was won by George Hadfield, who laid out the barracks and the house in a quadrangle. The barracks were established in 1801, the house, home of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, was completed in 1806. It is the oldest public building in continuous use in the nation’s capital.

Marine Corps traditions holds that when Washington was burned by the British during the War of 1812, both the Commandant’s House and the barracks were spared out of respect for the bravery shown by Marines during the Battle for Bladensburg.

Today, 8th and I is home to one of the most dramatic military celebrations in the world -- The Evening Parade. Held every Friday evening from May through August, the Evening Parade features “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band, “The Commandant’s Own” The United States Marine Drum and Bugle Corps, and the Marine Corps Silent Drill Platoon. It has become a lasting symbol of the professionalism, discipline, and esprit de Corps of the United States Marines, a celebration of the pride taken in a history that spans more than 230 years.

The Eagle, Globe and Anchor

The origins of the eagle, globe, and anchor insignia worn by Marines can be traced to those ornaments worn by early Continental Marines as well as to the British Royal Marines.

In 1776, Marines wore a device depicting a fouled anchor. Changes were made to that device in 1798, 1821, and 1824. An eagle was added in 1834. The current insignia dates to 1868 when Brigadier General Commandant Jacob Zeilin convened a board “to decide and report upon the various devices of cap ornaments of the Marine Corps.” A new insignia was recommended and approved by the Commandant. On 19 November 1868, the new insignia was accepted by the Secretary of the Navy.

The new emblem featured a globe showing the western hemisphere intersected by a fouled anchor and surmounted by an eagle. Atop the device, a ribbon was inscribed with the Latin motto “Semper Fidelis.” The globe signified the service of the United States Marines throughout the world. The anchor was indicative of the amphibious nature of the Marine Corps. The eagle, symbolizing a proud nation, was not the American bald eagle, but rather a crested eagle, a species found throughout the world.

On 22 June 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed an Executive Order which approved the design of an official seal for the United States Marine Corps. Designed at the request of General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., Commandant of the Marine Corps, the seal replaced the crested eagle with the American bald eagle, its wings proudly displayed. With the approval of this seal by the President of the United States in 1955, the emblem centered on the seal was adopted as the official Marine Corps emblem.

The eagle, globe, and anchor insignia is a testament to the training of the individual Marine, to the history and traditions of the Marine Corps, and to the values upheld by the Corps. It represents “those intangible possessions that cannot be issued: pride, honor, integrity, and being able to carry on the traditions for generations of warriors past.” Said retired Sergeant Major David W. Sommers, “the emblem of the Corps is the common thread that binds all Marines together, officer and enlisted, past and present…The eagle, globe and anchor tells the world who we are, what we stand for, and what we are capable of, in a single glance.”

The Marine Hymn

Following the Barbary Wars of 1805, the Colors of the Corps were inscribed with the words “to the shores of Tripoli.” After the capture and occupation of Mexico City in 1847, the Colors were changed to read “from the shores of Tripoli to the Halls of Montezuma.” These events in Marine Corps history are the origin of the opening words of the Marines’ Hymn.

Tradition holds that the words to the Marines’ Hymn were written by a Marine serving in Mexico. In truth, the author of the words remains unknown. Colonel Albert S. McLemore and Walter F. Smith, Assistant Band Director during the John Philip Sousa era, sought to trace the melody to its origins. It was reported to Colonel McLemore that by 1878 the tune was very popular in Paris, originally appearing as an aria in the Jacques Offenbach opera Genevieve de Brabant. John Philips Sousa later confirmed this belief in a letter to Major Harold Wirgman, USMC, stating “The melody of the ‘Halls of Montezuma’ is taken from Offenbach’s comic opera...”

Its origins notwithstanding, the hymn saw widespread use by the mid-1800s. Copyright ownership of the hymn was given to the Marine Corps per certificate of registration dated 19 August 1891. In 1929, it became the official hymn of the United States Marine Corps with the verses shown on the right.

On 21 November 1942, the Commandant of the Marine Corps authorized an official change in the first verse, fourth line, to reflect the changing mission of the Marine Corps. The new line read "in the air, on land and sea." That change was originally proposed by Gunnery Sergeant H.L. Tallman, an aviator and veteran of World War I.

Shortly after World War II, Marines began to stand at attention during the playing of The Marines’ Hymn, Today that tradition continues today to honor all those who have earned the title "United States Marine."

00:00

00:00

The Marines' Hymn

From the Halls of Montezuma

to the Shores of Tripoli,

We fight our country’s battles

On the land as on the sea.

First to fight for right and freedom,

And to keep our honor clean,

We are proud to claim the title

of United States Marine.

"Our flag’s unfurl’d to every breeze

From dawn to setting sun;

We have fought in every clime and place

Where we could take a gun.

In the snow of far-off northern lands

And in sunny tropic scenes,

You will find us always on the job

The United States Marines.

"Here’s health to you and to our Corps

Which we are proud to serve;

In many a strife we’ve fought for life

And never lost our nerve.

If the Army and the Navy

Ever look on Heaven’s scenes,

They will find the streets are guarded

By United States Marines."

The Battle of Chosin Reservoir, also known as the Chosin Reservoir Campaign or the Battle of Lake Jangjin (Korean: 장진호 전투; Hanja: 長津湖戰鬪; RR: Jangjinho jeontu; MR: Changjinho chŏnt'u), was an important battle in the Korean War.[c] The name "Chosin" is derived from the Japanese pronunciation "Chōshin", instead of the Korean pronunciation.[10]

Official Chinese sources refer to this battle as the eastern part of the Second Phase Campaign (or Offensive) (Chinese: 第二次战役东线; pinyin: Dì'èrcì Zhànyì Dōngxiàn). The western half of the Second Phase Campaign resulted in a Chinese victory in the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River.

The battle took place about a month after the People's Republic of China entered the conflict and sent the People's Volunteer Army (PVA) 9th Army[d] to infiltrate the northeastern part of North Korea. On 27 November 1950, the Chinese force surprised the US X Corps commanded by Major General Edward Almond at the Chosin Reservoir area. A brutal 17-day battle in freezing weather soon followed. Between 27 November and 13 December, 30,000[2] United Nations Command troops (later nicknamed "The Chosin Few") under the field command of Major General Oliver P. Smith were encircled and attacked by about 120,000[4] Chinese troops under the command of Song Shilun, who had been ordered by Mao Zedong to destroy the UN forces. The UN forces were nevertheless able to break out of the encirclement and to make a fighting withdrawal to the port of Hungnam, inflicting heavy casualties on the Chinese. US Marine units were supported in their withdrawal by the US Army's Task Force Faith to their east, which suffered heavy casualties and the full brunt of the Chinese offensive. The retreat of the US Eighth Army from northwest Korea in the aftermath of the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River and the evacuation of the X Corps from the port of Hungnam in northeast Korea marked the complete withdrawal of UN troops from North Korea.

By mid-October 1950, after the successful landing at Inchon by the US X Corps, the Eighth Army breakout from the Pusan Perimeter and the subsequent pursuit and destruction of the Korean People's Army (KPA), the Korean War appeared to be all but over.[11] United Nations (UN) forces advanced rapidly into North Korea with the intention of reuniting North and South Korea before the end of 1950.[12] North Korea is divided through the center by the impassable Taebaek Mountains, which separated the UN forces into two groups.[13] The US Eighth Army advanced north through the western coast of the Korean Peninsula, while the Republic of Korea (ROK) I Corps and the US X Corps advanced north on the eastern coast.[13]

At the same time the People's Republic of China entered the conflict after issuing several warnings to the United Nations.[14] On 19 October 1950, large formations of Chinese troops, dubbed the People's Volunteer Army (PVA), secretly crossed the border and into North Korea.[15] One of the first Chinese units to reach the Chosin Reservoir area was the PVA 42nd Corps, and it was tasked with stopping the eastern UN advances.[16] On 25 October, the advancing ROK I Corps made contact with the Chinese and halted at Funchilin Pass (40.204°N 127.3°E), south of the Chosin Reservoir.[17] After the landing at Wonsan, the US 1st Marine Division of the X Corps engaged the defending PVA 124th Division on 2 November, and the ensuing battle caused heavy casualties among the Chinese.[18] On 6 November, the PVA 42nd Corps ordered a retreat to the north with the intention of luring the UN forces into the Chosin Reservoir.[19] By 24 November, the 1st Marine Division occupied both Sinhung-ni [e] (40.557°N 127.27°E) on the eastern side of the reservoir and Yudami-ni (40.48°N 127.112°E) on the west side of the reservoir.[20]

Faced with the sudden attacks by Chinese forces in the Eighth Army sector, General Douglas MacArthur ordered the Eighth Army to launch the Home-by-Christmas Offensive.[21] To support the offensive, MacArthur ordered the X Corps to attack west from the Chosin Reservoir and to cut the vital Manpojin—Kanggye—Huichon supply line.[22][23] As a response, Major General Edward M. Almond, commander of the US X Corps, formulated a plan on 21 November. It called for the US 1st Marine Division to advance west through Yudami-ni, while the US 7th Infantry Division would provide a regimental combat team to protect the right flank at Sinhung-ni. The US 3rd Infantry Division would also protect the left flank while providing security in the rear area.[24] By then the X Corps was stretched thin along a 400-mile front.[20]

Surprised by the Marine landing at Wonsan,[25] Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong called for the immediate destruction of the ROK Capital Division, ROK 3rd Infantry Division, US 1st Marine Division, and US 7th Infantry Division in a telegraph to Commander[f] Song Shilun of the PVA 9th Army on 31 October.[26] Under Mao's urgent orders, the 9th Army was rushed into North Korea on 10 November.[27] Undetected by UN intelligence,[28] the 9th Army quietly entered the Chosin Reservoir area on 17 November, with the 20th Corps of the 9th Army relieving the 42nd Corps near Yudami-ni.[19]

Prelude

Location, terrain and weather

Chosin Reservoir is a man-made lake located in the northeast of the Korean peninsula.[29] The name Chosin is the Japanese pronunciation of the Korean place name Changjin, and the name stuck due to the outdated Japanese maps used by UN forces.[30] The battle's main focus was around the 78-mile (126 km) long road that connects Hungnam and Chosin Reservoir,[31] which served as the only retreat route for the UN forces.[32] Through these roads, Yudami-ni and Sinhung-ni,[e] located at the west and east side of the reservoir respectively, are connected at Hagaru-ri (now Changjin-ŭp) (40.3838°N 127.249°E). From there, the road passes through Koto-ri (40.284°N 127.3°E) and eventually leads to the port of Hungnam.[33] The area around the Chosin Reservoir was sparsely populated.[34]

The battle was fought over some of the roughest terrain during some of the harshest winter weather conditions of the Korean War.[2] The road was created by cutting through the hilly terrain of Korea, with steep climbs and drops. Dominant peaks, such as the Funchilin Pass and the Toktong Pass (40.3938°N 127.161°E), overlook the entire length of the road. The road's quality was poor, and in some places it was reduced to a one lane gravel trail.[33] On 14 November 1950, a cold front from Siberia descended over the Chosin Reservoir, and the temperature plunged, according to estimates, to as low as −36 °F (−38 °C).[35] The cold weather was accompanied by frozen ground, creating considerable danger of frostbite casualties, icy roads, and malfunctions. Medical supplies froze; morphine syrettes had to be defrosted in a medic's mouth before they could be injected; frozen blood plasma was useless on the battlefield. Even cutting off clothing to deal with a wound risked gangrene and frostbite. Batteries used for the Jeeps and radios did not function properly in the temperature and quickly ran down.[36] The lubrication in the guns gelled and rendered them useless in battle. Likewise, the springs on the firing pins would not strike hard enough to fire the round, or would jam.[37]

Aftermath

Casualties

The US X Corps and the ROK I Corps reported a total of 10,495 battle casualties: 4,385 US Marines, 3,163 US Army personnel, 2,812 South Koreans attached to American formations and 78 British Royal Marines.[189] The 1st Marine Division also reported 7,338 non-battle casualties due to the cold weather, adding up to a total of 17,833 casualties.[190] Despite the losses, the US X Corps preserved much of its strength.[191] About 105,000 soldiers, 98,000 civilians, 17,500 vehicles, and 350,000 tons of supplies were shipped from Hungnam to Pusan,[12]:367 and they would later rejoin the war effort in Korea. Commanding General Smith was credited for saving the US X Corps from destruction,[39]:430 while the 1st Marine Division, 41 Royal Marines Commando and RCT-31 were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for their tenacity during the battle.[192][193][194] Fourteen Marines, two soldiers and one Navy pilot received the Medal of Honor, and all of the UN troops that served at Chosin were later honored with the nickname "The Chosin Few".[192][195] On 15 September 2010, the Veterans of the Korean War Chosin Reservoir Battle memorial was unveiled by the United States Marine Corps Commandant General James T. Conway at Camp Pendleton.[196]

The PVA 9th Army suffered 19,202 combat casualties, and 28,954 non-combat casualties were attributed to the harsh Korean winter and lack of food. Total casualties thus amounted to 48,156 - about one third of its total strength.[7] Outside of official channels, the estimation of Chinese casualties has been described as high as 60,000 by Patrick C. Roe, the chairman of Chosin Few Historical Committee, citing the number of replacements requested by 9th Army in the aftermath of the battle.[197] Regardless of the varying estimates, historian Yan Xue of PLA National Defence University noted that the 9th Army was put out of action for three months.[198] With the absence of 9th Army the Chinese order of battle in Korea was reduced to 18 infantry divisions by December 31, 1950,[199] as opposed to the 30 infantry divisions present on November 16, 1950.[200]

Operation Glory

The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific where many of the UN war dead which were exchanged under Operation Glory are buried.

During the battle, UN dead were buried at temporary grave sites along the road. Operation Glory took place from July to November 1954, during which the dead of each side were exchanged. The remains of 4,167 US soldiers were exchanged for 13,528 North Korean and Chinese dead. In addition, 546 civilians who died in UN prisoner-of-war camps were turned over to the South Korean government.[201] After Operation Glory, 416 Korean War "unknowns" were buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (the "Punchbowl Cemetery" in Honolulu, Hawaii). According to a Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) white paper, 1,394 names were also transmitted from the Chinese and North Koreans during the operation, of which 858 proved to be correct.[202] The 4,167 returned remains were found to be 4,219 individuals, of whom 2,944 were found to be Americans, with all but 416 identified by name. Of the 239 Korean War unaccounted for, 186 are not associated with the Punchbowl Cemetery unknowns.[k] From 1990 to 1994, North Korea excavated and returned more than 208 sets of remains, which possibly include 200 to 400 US servicemen, but very few have been identified due to the co-mingling of remains.[203] From 2001 to 2005, more remains were recovered from the Chosin Battle site, and around 220 were recovered near the Chinese border between 1996 and 2006.[204][205]

Outcome assessment

Roy E. Appleman, the author of US Army official history South to Naktong, North to Yalu, writes that both sides could claim victory: the PVA 9th Army ultimately held the battlefield, while X Corps held off the PVA 9th Army in a series of battles that enabled it to withdraw most of its forces as an effective tactical unit.[206] Allan R. Millett qualifies a Chinese "geographic victory" that ejected X Corps from North Korea with the fact that the Chinese failed to achieve the objective of destroying the 1st Marine Division, adding that the campaign gave the UN confidence that it could withstand the superior numbers of the Chinese forces.[207] The official Chinese history, published by PLA Academy of Military Science, states that despite the heavy casualties, the PVA 9th Army had earned its victory by successfully protecting the eastern flank of Chinese forces in Korea, while inflicting over 10,000 casualties to the UN forces.[208]

Eliot A. Cohen writes that the retreat from Chosin was a UN victory which inflicted such heavy losses on the PVA 9th Army that it was put out of action until March 1951.[209] Paul M. Edwards, founder of the Center for the Study of the Korean War,[210] draws parallels between the battle at Chosin and the Dunkirk evacuation. He writes that the retreat from Chosin following a "massive strategic victory" by the Chinese has been represented as "a moment of heroic history" for the UN forces.[211] Appleman, on the other hand, questioned the necessity of a sea-borne evacuation to preserve the UN forces, asserting that X Corps had the strength to break out of the Chinese encirclement at Hungnam at the end of the battle.[212] Chinese historian Li Xiaobing acknowledges X Corps' successful withdrawal from North Korea, and writes that the Battle of Chosin "has become a part of Marine lore, but it was still a retreat, not a victory."[213] Bruce Cumings simply refers to the battle as a "terrible defeat" for the Americans.[214]

Patrick C. Roe, who served as an intelligence officer with the 7th Marine Regiment at Chosin,[215] asserts that X Corps directly allowed the Eighth Army to hold the south[l] and quoted MacArthur in corroborating his view.[m] Yu Bin, a historian and a former member of the Chinese People's Liberation Army, states that while the destruction of Task Force Faith[n] was viewed as the single greatest Chinese victory of the war, ultimately the PVA 9th Army had become "a giant hospital" while failing to destroy the numerically inferior UN forces at Chosin as planned.[216] Zhang Renchu, whose 26th Corps was blamed for allowing the X Corps to escape,[7] had threatened suicide over the outcome, while Song Shilun offered to resign his post.[217]

The battle exacerbated inter-service hostility, the Marines blaming the US Army and its leadership for the failure.[218] The collapse of the army units fighting on the east of the reservoir was regarded as shameful, and for many years afterwards their role in the battle was largely ignored. Later studies concluded that Task Force MacLean/Faith had held off for five days a significantly larger force than previously thought and that their stand was a significant factor in the Marines' survival. This was eventually recognized in September 1999 when, for its actions at Chosin, Task Force Faith was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, an award that General Smith blocked when it was first proposed in 1952.[219][220]

The Marines evacuated from North Korea spent January and most of February 1951 rebuilding in the relatively secure South Korea, where they destroyed the well-respected but already weakened North Korean 10th Division in counter-guerrilla operations during the Second Battle of Wonju.[22]:227[221] The Marines returned to regular and heavy action on February 21 in Operation Killer.[222]

Wider effect on the war

The battle ended the UN force's expectation of total victory, including the capture of North Korea and the reunification of the peninsula.[223] By the end of 1950, PVA/KPA forces had recaptured North Korea and pushed UN forces back south of the 38th parallel. Serious consideration was given to the evacuation of all US forces from the Korean peninsula and US military leaders made secret contingency plans to do so.[224] The disregard by Far Eastern Command under MacArthur of the initial warnings and diplomatic hints by the PVA almost led the entire UN army to disaster at Ch'ongch'on River and Chosin Reservoir and only after the formation and stabilization of a coherent UN defensive line under Lieutenant General Matthew Ridgway did the "period of headlong retreats from an attacking, unsuspected foe" cease.[223]

On the other hand, the battle affected the PVA in two ways, both of which had the result of helping the UN Command to secure its position in South Korea, while losing North Korea. First, according to historian Shu Guang Zhang, PVA commanders were persuaded by their victories at Chosin and Ch'ongch'on that they could "defeat American armed forces", and this led to "unrealistic expectations that the CPV [PVA] would work miracles."[225][39]:624–5 Second, the heavy casualties caused by sub-zero temperatures and combat, plus poor logistical support weakened the PVA's eight elite divisions of the 20th and 27th Corps. Of those eight divisions, two were forced to disband,[226] With the absence of 12 out of 30 of Chinese divisions in Korea in early 1951, Roe says that the heavy Chinese losses at Chosin enabled the UN forces to maintain a foothold in Korea.[227]

Legacy

The Battle of Chosin Reservoir is regarded by some historians as the most brutal in modern warfare by violence, casualty rate, weather conditions, and endurance.[228] Over the course of fourteen days, 17 Medals of Honor (Army and Navy) and 78 Service Cross Medals (Army and Navy) were awarded, the second most as of 2020 after the Battle of the Bulge (20MOHs / 83SCMs).[229][230]

Veterans of the battle are colloquially referred to as the "Chosin Few" and symbolized by the "Star of Koto-ri".[230]

American military leaders, including General Douglas MacArthur, were caught off guard by the entrance of the People’s Republic of China, led by Mao Zedong, into the five-month-old Korean War. Twelve thousand men of the First Marine Division, along with a few thousand Army soldiers, suddenly found themselves surrounded, outnumbered and at risk of annihilation at the Chosin Reservoir, high in the mountains of North Korea. The two-week battle that followed, fought in brutally cold temperatures, is one of the most celebrated in Marine Corps annals.